| Section 1.1: Full Text |

Chapter Contents

| View Full Text | View

Bullet Text |

| Why Information Systems Matter |

| How Much Does IT Matter? |

| Why IT Now? Digital Convergence and the Changing Business Environment |

DaimlerChrysler’s information systems use both technology and knowledge

of the business to enable the company and its suppliers to respond instantly

to changes in the marketplace or other events. These information systems

give DaimlerChrysler the agility to monitor and react to data as events

unfold, and they are intimately linked with systems of its suppliers and

related companies. Managers can “see into” these systems and,

when necessary, make adjustments on the fly to keep manufacturing and

delivery processes aligned with customer needs.

The agility

exhibited by DaimlerChrysler is part of the transformation of business

firms throughout the world into fully digital firms. Such digital firms

use the Internet and networking technology to make data flow seamlessly

among different parts of the organization; streamline the flow of work;

and create electronic links with customers, suppliers, and other organizations.

As a manager,

you’ll need to know how information systems can make your business

more competitive, efficient, and profitable. In this chapter we begin

our investigation of information systems and organizations by describing

information systems from both technical and behavioral perspectives and

by surveying the changes they are bringing to organizations and management.

Why Information Systems?

We are in the midst of a swiftly moving river of technology and business

innovations that is transforming the global business landscape. An entirely

new Internet business culture is emerging with profound implications for

the conduct of business. You can see this every day by observing how business

people work using high-speed Internet connections for e-mail and information

gathering, portable computers connected to wireless networks, cellular

telephones connected to the Internet, and hybrid handheld devices delivering

phone, Internet, and computing power to an increasingly mobile and global

workforce.

The emerging

Internet business culture is a set of expectations that we all share.

We have all come to expect online services for purchasing goods and services,

we expect our business colleagues to be available by e-mail and cell phone,

and we expect to be able to communicate with our vendors, customers, and

employees any time of day or night over the Internet. We even expect our

business partners around the world to be “fully connected.”

Internet culture is global.

In this text

and in the business world, you’ll often encounter the term information

technology. Information technology (abbreviated IT) refers to all of the

computer-based information systems used by organizations and their underlying

technologies. Briefly, information technologies and systems are revolutionizing

the operation of firms, industries, and markets. The main objective of

this book is to describe the nature of this transformation and to help

you as a future manager take advantage of the emerging opportunities.

Why Information Systems Matter

Let’s start by examining why information systems and information

technology (IT) are so important. There are four reasons why IT will make

a difference to you as a manager throughout your career.

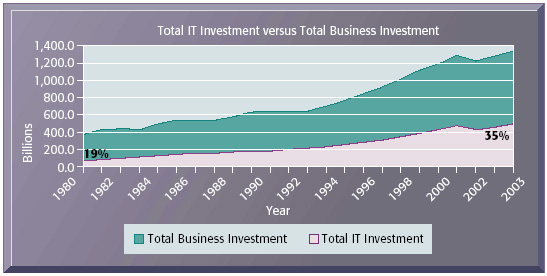

CAPITAL MANAGEMENT

Information technology has become the largest component of capital investment

for firms in the United States and many industrialized societies. In 2005,

U.S. firms alone will spend nearly $1.8 trillion on IT and telecommunications

equipment and software. Investment in information technology has doubled

as a percentage of total business investment since 1980, and now accounts

for more than one-third of all capital invested in the United States and

more than 50 percent of invested capital in information-intensive industries,

such as finance, insurance, and real estate.

Figure 1-1

shows that between 1980 and 2003, private business investment in information

technology (hardware, software, and telecommunications equipment) grew

from 19 percent to more than 35 percent of all domestic private business

investment. If one included expenditures for managerial and organizational

change programs and business and consulting services that are required

to use this technology effectively, total information technology expenditures

would rise above 50 percent of total private business investment.

|

|

FIGURE 1-1 Information technology capital

investment |

As managers, many of you will work for firms that are intensively using information systems and making large investments in information technology. You will certainly want to know how to invest this money wisely. If you make wise choices, your firm can outperform competitors. If you make poor choices, you will be wasting valuable capital. This book is dedicated to helping you make wise decisions about IT and information systems.

In the United States over 23 million managers and over 113 million workers in the labor force rely on information systems every day to conduct business (Statistical Abstract, 2003). In many industries, survival and even existence without extensive use of information systems is inconceivable. Obviously, all of e-commerce would be impossible without substantial IT investments, and firms such as Amazon, eBay, Google, E*Trade, or the world’s largest online university, the University of Phoenix, simply would not exist. Today’s service industries—finance, insurance, real estate as well as personal services such as travel, medicine, and education—could not operate without IT. Similarly, retail firms such as Wal-Mart and Sears and manufacturing firms such as General Motors and General Electric require IT to survive and prosper. Just like offices, telephones, filing cabinets, and efficient tall buildings with elevators were once of the foundations of business in the twentieth century, information technology is a foundation for business in the twenty-first century.

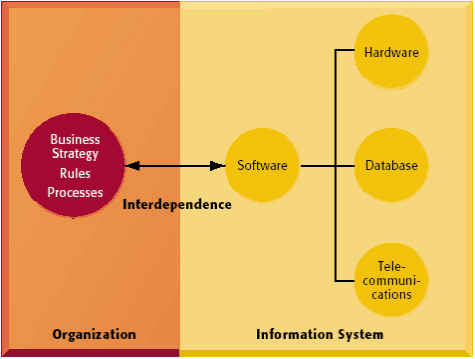

There is a growing interdependence between a firm’s ability to use information technology and its ability to implement corporate strategies and achieve corporate goals (see Figure 1-2). What a business would like to do in five years often depends on what its systems will be able to do. Increasing market share, becoming the high-quality or low-cost producer, developing new products, and increasing employee productivity depend more and more on the kinds and quality of information systems in the organization. The more you understand about this relationship, the more valuable you will be as a manager.

|

FIGURE 1-2 The interdependence between organizations and information systems. In contemporary systems there is a growing interdependence between a firm’s information systems and its business capabilities. Changes in strategy, rules, and business processes increasingly require changes in hardware, software, databases, and telecommunications. Often, what the organization would like to do depends on what its systems will permit it to do. |

PRODUCTIVITY

Today’s managers have very few tools at their disposal for achieving significant gains in productivity. IT is one of the most important tools along with innovations in organization and management, and in fact, these innovations need to be linked together. A substantial and growing body of research reported throughout this book suggests investment in IT plays a critical role in increasing the productivity of firms, and entire nations (Zhu et al., 2004).

For instance,

economists at the U.S. Federal Reserve Bank estimate that IT contributed

to the lowering of inflation by 0.5 to 1 percentage point in the years

from 1995 to 2000 (Greenspan, 2000). IT was a major factor in the resurgence

in productivity growth in the United States, which began in 1995 and has

continued until today at an average rate of 2.7 percent, up from 1.4 percent

from 1973 to 1995 (Baily, 2002). Firms that invested wisely in information

technology experienced continued growth in productivity and efficiency.

STRATEGIC OPPORTUNITY AND ADVANTAGE

If you want to take advantage of new opportunities in markets, develop

new products, and create new services, chances are quite high you will

need to make substantial investments in IT to realize these new business

opportunities. If you want to achieve a strategic advantage over your

rivals, to differentiate yourself from your competitors, IT is one avenue

for achieving such advantages along with changes in business practices

and management. We talk more about IT contributions to competitive strategy

in Chapter 3. These advantages might not last forever, but then again

most strategic advantages throughout history are short-lived. However,

a string of short-lived competitive advantages is a foundation for long-term

advantages in business, just as is true of any athletic sport or race.

How Much Does IT Matter?

In May 2003, Nicholas Carr, an editor at Harvard Business

Review, wrote an article titled “IT Doesn’t Matter,”

which stirred significant debate in the business community. Carr’s

argument in a nutshell is that because every firm can purchase IT in the

marketplace, because any advantage obtained by one company can easily

be copied by another company, and because IT is now a commodity based

on standards (such as the Internet) that all companies can freely use,

it is no longer a differentiating factor in organizational performance.

Carr argues

that no firm can use IT to achieve a strategic edge over its competitors

any more than it could with electricity, telephones, or other infrastructure.

Therefore, Carr concludes, firms should reduce spending on IT, follow

rather than lead IT in their industry, reduce risks by preparing for computer

outages and security breaches, and avoid deploying IT in new ways.

Most management

information system (MIS) experts disagree. As we discuss later in this

chapter and subsequent chapters throughout the book, research demonstrates

that there is considerable variation in firms’ ability to use IT

effectively. Many highly adept firms continually obtain superior returns

on their investment in IT, whereas less adept firms do not.

Copying innovations

of other firms can be devilishly difficult, with much being lost in the

translation. There is only one Dell, one Wal-Mart, one Amazon, and one

eBay, and each of these firms has achieved a competitive advantage in

its industry based in large part on unique ways of organizing work enabled

by IT that have been very difficult to copy. If copying were so easy,

we would expect to find much more powerful competition for these market

leaders.

Although

falling prices for hardware and software and new computing and telecommunications

standards such as the Internet have made the application of computers

to business much easier than in the past, this does not signal the end

of innovation or the end of firms developing strategic edges using IT.

Far from the end of innovation, commoditization often leads to an explosion

in innovation and new markets and products. For example, the abundance

and availability of materials such as wood, glass, and steel during the

last century made possible a continuing stream of architectural innovation.

Likewise,

the development of standards and lowering costs of computer hardware made

possible new products and services such as the Apple iPod and iTunes,

the Sony Walkman portable music player, RealMedia online streaming music,

and the entire online content industry. Entirely new businesses and business

models have emerged for the digital distribution of music, books, journals,

and Hollywood films.

Carr is surely

correct in stating that not all investments in IT work out or have strategic

value. Some are just needed to stay in business, to comply with government

reporting requirements, and to satisfy the needs of customers and vendors.

Perhaps the more important questions are how much does IT make a difference,

and where can it best be deployed to make a competitive difference?

We make a

major effort in this book to suggest ways you as a manager and potential

entrepreneur can use information technology and systems to create differentiation

from your competitors and strategic advantage in the marketplace. As we

describe throughout, to achieve any measure of “success,”

investment in IT must be accompanied by significant changes in business

operations and processes and changes in management culture, attitudes,

and behavior. Absent these changes, investment in IT can be a waste of

precious investor resources.

Why IT Now? Digital Convergence and the Changing Business Environment

A combination of information technology innovations

and a changing domestic and global business environment makes the role

of IT in business even more important for managers than just a few years

ago. The Internet revolution is not something that happened and then burst,

but instead has turned out to be an ongoing, powerful source of new technologies

with significant business implications for much of this century.

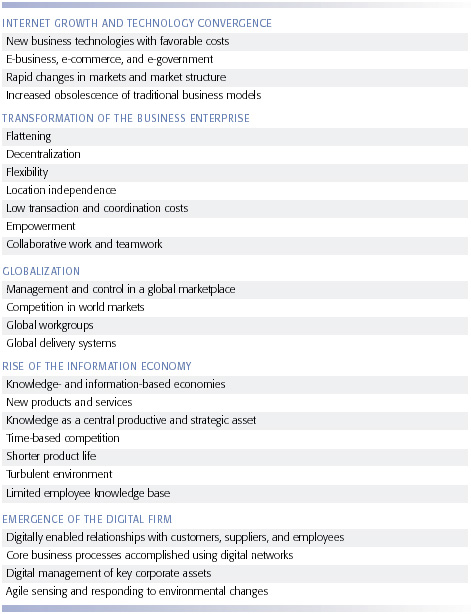

There are five factors to consider when assessing the growing impact of IT in business

firms both today and over the next ten years.

- Internet growth and technology convergence

- Transformation of the business enterprise

- Growth of a globally connected economy

- Growth of knowledge and information-based economies

- Emergence of the digital firm

| TABLE 1-1

The Changing Contemporary Business Environment |

|

THE INTERNET AND TECHNOLOGY CONVERGENCE

One of the most frequently asked questions by Wall Street investors, journalists, and business entrepreneurs is, “What’s the next big thing?” As it turns out, the next big thing is in front of us: We are in the midst of a networking and communications revolution driven by the growth of the Internet, Internet-based technologies, and new business models and processes that leverage the new technologies.

Although “digital convergence” was predicted a decade ago,

it is now an undeniable reality. Four massive industries are moving toward

a common platform: the $1 trillion computer hardware and software industry

in the United States, the $250 billion consumer electronics industry,

the $1.6 trillion communications industry (traditional and wireless telephone

networks), and the $900 billion content industry (from Hollywood movies,

to music, text, and research industries). Although each industry has its

favored platform, the outlines of the future are clear: a world of near

universal, online, on-demand, and personalized information services from

text messaging on cell phones, to games, education, and entertainment.

The Internet

is bringing about a convergence of technologies, roiling markets, entire

industries, and firms in the process. Traditional boundaries and business

relationships are breaking down, even as new ones spring up. Telephone

networks are merging into the Internet, and cellular phones are becoming

Internet access devices. Handheld storage devices such as iPods are emerging

as potential portable game and entertainment centers. The Internet-connected

personal computer is moving toward a role as home entertainment control

center.

Traditional

markets and distribution channels are weakening and new markets are being

created. For instance, the markets for music CDs and video DVDs and the

music and video store industries are undergoing rapid change. New markets

for online streaming media and for music and video downloads have materialized.

Today, networking

and the Internet are nearly synonymous with doing business. Firms’

relationships with customers, employees, suppliers, and logistic partners

are becoming digital relationships. As a supplier, you cannot do business

with Wal-Mart, or Sears, or most national retailers unless you adopt their

well-defined digital technologies. As a consumer, you will increasingly

interact with sellers in a digital environment. As an employer, you’ll

be interacting more electronically with your employees and giving them

new digital tools to accomplish their work.

So much business

is now enabled by or based upon digital networks that we use the terms

electronic business and electronic commerce frequently throughout this

text. Electronic business, or e-business, designates the use of Internet

and digital technology to execute all of the activities in the enterprise.

E-business includes activities for the internal management of the firm

and for coordination with suppliers and other business partners. It also

includes electronic commerce, or e-commerce. E-commerce is the part of

e-business that deals with the buying and selling of goods and services

electronically with computerized business transactions using the Internet,

networks, and other digital technologies. It also encompasses activities

supporting those market transactions, such as advertising, marketing,

customer support, delivery, and payment.

The technologies

associated with e-commerce and e-business have also brought about similar

changes in the public sector. Governments on all levels are using Internet

technology to deliver information and services to citizens, employees,

and businesses with which they work. E-government is the application of

the Internet and related technologies to digitally enable government and

public sector agencies’ relationships with citizens, businesses,

and other arms of government. In addition to improving delivery of government

services, e-government can make government operations more efficient and

also empower citizens by giving them easier access to information and

the ability to network electronically with other citizens. For example,

citizens in some states can renew their driver’s licenses or apply

for unemployment benefits online, and the Internet has become a powerful

tool for instantly mobilizing interest groups for political action and

fund-raising.

Along with rapid changes in markets and competitive advantage are changes in the firms themselves. The Internet and the new markets are changing the cost and revenue structure of traditional firms and are hastening the demise of traditional business models.

For instance, in the United States, 20 percent of travel sales are made online, and experts believe that 50 to 70 percent of travel sales will be online within a decade. Realtors have had to reduce commissions on home sales because of competition from Internet real estate sites. The business model of traditional local telephone companies, and the value of their copper-based networks, is rapidly declining as millions of consumers switch to cellular and Internet telephones. At current rates of decline in subscribers, about 15 percent per year, the value of traditional local phone networks will decline by 50 percent by 2010 (Brown and Latour, 2004).

The Internet and related technologies make it possible to conduct business across firm boundaries almost as efficiently and effectively as it is to conduct business within the firm. This means that firms are no longer limited by traditional organizational boundaries or physical locations in how they design, develop, and produce goods and services. It is possible to maintain close relationships with suppliers and other business partners at great distances and outsource work that firms formerly did themselves to other companies.

For example, Cisco Systems does not manufacture the networking products it sells; it uses other companies, such as Flextronics, for this purpose. Cisco uses the Internet to transmit orders to Flextronics and to monitor the status of orders as they are shipped. GKN Aerospace North America, which fabricates engine parts for aircraft and aerospace vehicles, uses a system called Sentinel with a Web interface to monitor key indicators of the production systems of Boeing Corporation, its main customer. Sentinel responds automatically to Boeing’s need for parts by increasing, decreasing, or shutting down GKN’s systems according to parts usage (Mayor, 2004).

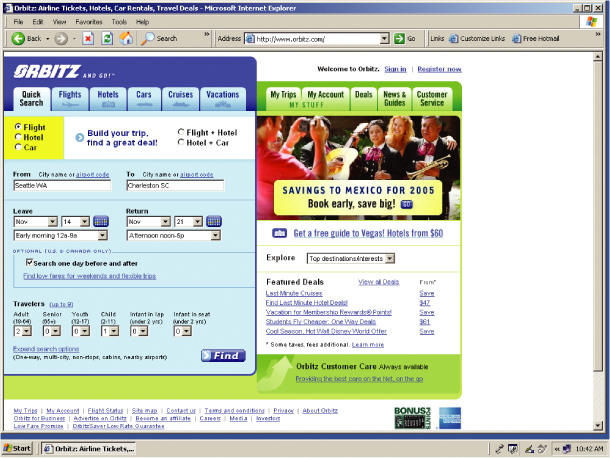

|

At

the Orbitz Web site, visitors can make online reservations for airlines,

hotels, rental cars, cruises, and vacation packages and obtain information

on travel and leisure topics. Such online travel services are supplanting

traditional travel agencies. |

In addition to these changes, there has also been a transformation in

the management of the enterprise. The traditional business firm was—and

still is—a hierarchical, centralized, structured arrangement of

specialists who typically relied on a fixed set of standard operating

procedures to deliver a mass-produced product (or service). The new style

of business firm is a flattened (less hierarchical), decentralized, flexible

arrangement of generalists who rely on nearly instant information to deliver

mass-customized products and services uniquely suited to specific markets

or customers.

The traditional

management group relied—and still relies—on formal plans,

a rigid division of labor, and formal rules. The new manager relies on

informal commitments and networks to establish goals (rather than formal

planning), a flexible arrangement of teams and individuals working in

task forces, and a customer orientation to achieve coordination among

employees. The new manager appeals to the knowledge, learning, and decision

making of individual employees to ensure proper operation of the firm.

Once again, information technology makes this style of management possible.

GLOBALIZATION

A growing percentage of the American economy—and other advanced

industrial economies in Europe and Asia—depends on imports and exports.

Foreign trade, both exports and imports, accounts for more than 25 percent

of the goods and services produced in the United States, and even more

in countries such as Japan and Germany. Companies are also distributing

core business functions in product design, manufacturing, finance, and

customer support to locations in other countries where the work can be

performed more cost effectively. The success of firms today and in the

future depends on their ability to operate globally.

Today, information

systems provide the communication and analytic power that firms need to

conduct trade and manage businesses on a global scale. Controlling the

far-flung global corporation—communicating with distributors and

suppliers, operating 24 hours a day in different national environments,

coordinating global work teams, and servicing local and international

reporting needs—is a major business challenge that requires powerful

information system responses.

Globalization

and information technology also bring new threats to domestic business

firms: Because of global communication and management systems, customers

now can shop in a worldwide marketplace, obtaining price and quality information

reliably 24 hours a day. To become competitive participants in international

markets, firms need powerful information and communication systems.

RISE OF THE INFORMATION ECONOMY

The United States, Japan, Germany, and other major industrial powers are

being transformed from industrial economies to knowledge-and information-based

service economies, whereas manufacturing has been moving to lower-wage

countries. In a knowledge-and information-based economy, knowledge and

information are key ingredients in creating wealth.

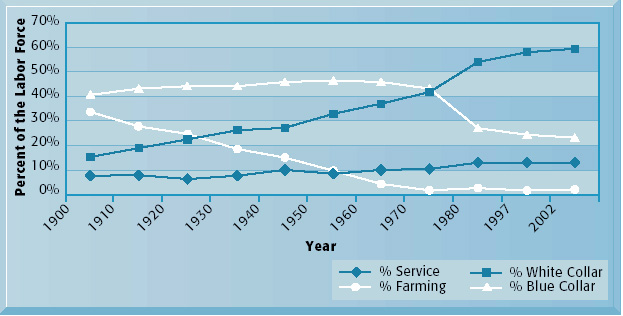

The knowledge

and information revolution began at the turn of the twentieth century

and has gradually accelerated. By 1976, the number of white-collar workers

employed in offices surpassed the number of farm workers, service workers,

and blue-collar workers employed in manufacturing (see Figure 1-3). Today,

most people no longer work on farms or in factories but instead are found

in sales, education, health care, banks, insurance firms, and law firms;

they also provide business services, such as copying, computer programming,

or making deliveries. These jobs primarily involve working with, distributing,

or creating new knowledge and information. In fact, knowledge and information

work now account for a significant 60 percent of the U.S. gross national

product and nearly 55 percent of the labor force.

|

| FIGURE 1-3 The growth of the information economy Since the beginning of the twentieth century, the United States has experienced a steady decline in the number of farm workers and blue-collar workers who are employed in factories. At the same time, the country is experiencing a rise in the number of white-collar workers who produce economic value using knowledge and information. Source: U.S. Department of Commerce, Bureau of the Census, Statistical Abstract of the United States, 2003, Table 615; and Historical Statistics of the United States, Colonial Times to 1970, Vol. 1, Series D, pp. 182–232.. |

In knowledge-and information-based economies, the market value of many

firms is based largely on intangible assets, such as proprietary knowledge,

information, unique business methods, brands, and other “intellectual

capital.” Physical assets, such as buildings, machinery, tools,

and inventory, now account for less than 20 percent of the market value

of many public firms in the United States (Lev, 2001).

Knowledge

and information provide the foundation for valuable new products and services,

such as credit cards, overnight package delivery, or worldwide reservation

systems. Knowledge- and information-intense products, such as computer

games, require a great deal of knowledge to produce, and knowledge is

used more intensively in the production of traditional products as well.

In the automobile industry, for instance, both design and production now

rely heavily on knowledge and information technology.

EMERGENCE OF THE DIGITAL FIRM

All of the changes we have just described, coupled with equally significant

organizational redesign, have created the conditions for a fully digital

firm. The digital firm can be defined along several dimensions. A digital

firm is one in which nearly all of the organization’s significant

business relationships with customers, suppliers, and employees are digitally

enabled and mediated. Core business processes are accomplished through

digital networks spanning the entire organization or linking multiple

organizations.

Business processes refer to the set of logically related tasks and behaviors

that organizations develop over time to produce specific business results

and the unique manner in which these activities are organized and coordinated.

Developing a new product, generating and fulfilling an order, creating

a marketing plan, and hiring an employee are examples of business processes,

and the ways organizations accomplish their business processes can be

a source of competitive strength. (A detailed discussion of business processes

can be found in Chapter 2.)

Key corporate

assets—intellectual property, core competencies, and financial and

human assets—are managed through digital means. In a digital firm,

any piece of information required to support key business decisions is

available at any time and anywhere in the firm.

Digital firms

sense and respond to their environments far more rapidly than traditional

firms, giving them more flexibility to survive in turbulent times. Digital

firms offer extraordinary opportunities for more global organization and

management. By digitally enabling and streamlining their work, digital

firms have the potential to achieve unprecedented levels of profitability

and competitiveness. DaimlerChrysler, described earlier, illustrates some

of these qualities. Electronically integrating key business processes

with suppliers has made this company much more agile and adaptive to customer

demands and changes in its supplier network.

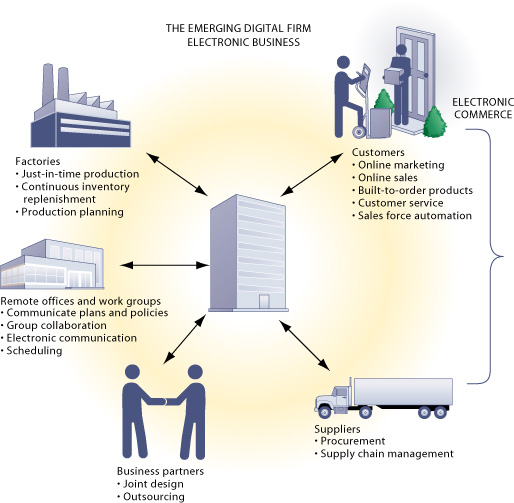

Figure 1-4

illustrates a digital firm making intensive use of Internet and digital

technology for electronic business. Information can flow seamlessly among

different parts of the company and between the company and external entities—its

customers, suppliers, and business partners. More and more organizations

are moving toward this digital firm vision.

|

FIGURE

1-4 Electronic business and electronic commerce in the emerging

digital firm Companies can use Internet technology for e-commerce transactions with customers and suppliers, for managing internal business processes, and for coordinating with suppliers and other business partners. E-business includes e-commerce as well the management and coordination of the enterprise. |

A

few firms, such as Cisco Systems or Dell Computers, are close to becoming

fully digital firms, using the Internet to drive every aspect of their

business. In most other companies, a fully digital firm is still more

vision than reality, but this vision is driving them toward digital integration.

Firms are continuing to invest heavily in information systems that integrate

internal business processes and build closer links with suppliers and

customers.

The Window on Organizations

describes such a digital firm in the making. Cemex, a world-leading global

cement and construction materials firm, has achieved impressive results

through ruthless focus on operational excellence. Management took an enterprise-wide

view of its business processes and developed a series of information systems

to turn the company into a lean, efficient, agile machine that could instantly

respond to changes in customer orders, weather, and other last-minute

events.