| Section 1.2: Full Text | Chapter

Contents | View Full Text | View

Bullet Text |

| What Is an Information System? |

| Window on Organizations |

| Window on Technology |

| It Isn’t Just Technology: A Business Perspective on Information Systems |

| Dimensions of Information Systems |

PERSPECTIVES ON INFORMATION SYSTEMS

Information systems can be best be understood by looking at them from both a technology and a business perspective.

What Is an Information System?

An information system can be defined technically as

a set of interrelated components that collect (or retrieve), process,

store, and distribute information to support decision making and control

in an organization. In addition to supporting decision making, coordination,

and control, information systems may also help managers and workers analyze

problems, visualize complex subjects, and create new products.

Information

systems contain information about significant people, places, and things

within the organization or in the environment surrounding it. By information

we mean data that have been shaped into a form that is meaningful and

useful to human beings. Data, in contrast, are streams of raw facts representing

events occurring in organizations or the physical environment before they

have been organized and arranged into a form that people can understand

and use.

Cemex uses a sophisticated

scheduling system to expedite cement delivery. Cemex manages deliveries

and all of its manufacturing and production processes from a highly

computerized control room. The company is moving toward a digital

firm organization. |

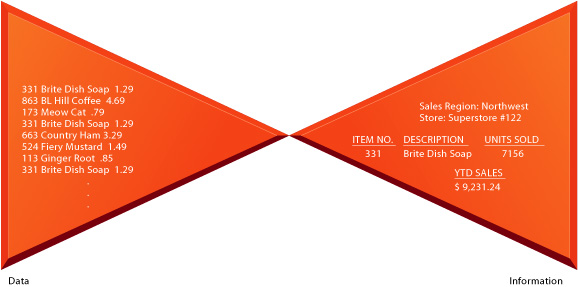

A brief example contrasting information and data may prove useful. Supermarket checkout counters ring up millions of pieces of data, such as product identification numbers or the cost of each item sold. Such pieces of data can be totaled and analyzed to provide meaningful information, such as the total number of bottles of dish detergent sold at a particular store, which brands of dish detergent were selling the most rapidly at that store or sales territory, or the total amount spent on that brand of dish detergent at that store or sales region (see Figure 1-5).

|

FIGURE 1-5

Data and information Raw data from a supermarket checkout counter can be processed and organized to produce meaningful information such as the total unit sales of dish detergent or the total sales revenue from dish detergent for a specific store or sales territory. |

Three activities in an information system produce the information that organizations need to make decisions, control operations, analyze problems, and create new products or services. These activities are input, processing, and output (see Figure 1-6). Input captures or collects raw data from within the organization or from its external environment. Processing converts this raw input into a more meaningful form. Output transfers the processed information to the people who will use it or to the activities for which it will be used. Information systems also require feedback, which is output that is returned to appropriate members of the organization to help them evaluate or correct the input stage.

|

FIGURE 1-6

Functions of an information system

An information system contains information about an organization and its surrounding environment. Three basic activities—input, processing, and output—produce the information organizations need. Feedback is output returned to appropriate people or activities in the organization to evaluate and refine the input. Environmental factors such as customers, suppliers, competitors, stockholders, and regulatory agencies interact with the organization and its information systems. |

In DaimlerChrysler’s Integrated Volume Planning system, raw input consists of dealer identification number, model, color, and optional features of cars ordered from dealers. DaimlerChrysler’s computers store these data and process them to anticipate how many new vehicles to manufacture for each model, color, and option package. The output would consist of orders to suppliers specifying the quantity of each part or component that was needed and the exact date each part was to be delivered to DaimlerChrysler’s production facilities to produce the vehicles that customers have ordered. The system provides meaningful information such as what models, colors, and options are selling in which locations; the most popular models and colors; and which dealers sell the most cars and trucks.

Our interest in this book is in formal, organizational computer-based information systems, such as those designed and used by DaimlerChrysler and its suppliers. Formal systems rest on accepted and fixed definitions of data and procedures for collecting, storing, processing, disseminating, and using these data. The formal systems we describe in this text are structured; that is, they operate in conformity with predefined rules that are relatively fixed and not easily changed. For instance, DaimlerChrysler’s Integrated Volume Planning system would require unique numbers or codes for identifying each vehicle part or component and each supplier.

Informal information systems (such as office gossip networks) rely, by contrast, on unstated rules of behavior. There is no agreement on what is information or on how it will be stored and processed. Such systems are essential for the life of an organization, but an analysis of their qualities is beyond the scope of this text.

Formal information systems can be either computer based or manual. Manual systems use paper-and-pencil technology. These manual systems serve important needs, but they too are not the subject of this text. Computer-based information systems (CBIS), in contrast, rely on computer hardware and software technology to process and disseminate information. From this point on, when we use the term information systems, we are referring to computer-based information systems—formal organizational systems that rely on computer technology.

The Window on Technology describes some of the typical technologies used in computer-based information systems today. United Parcel Service (UPS) invests heavily in information systems technology to make its business more efficient and customer-oriented. It uses an array of information technologies including bar-code scanning systems, wireless networks, large mainframe computers, handheld computers, the Internet, and many different pieces of software for tracking packages, calculating fees, maintaining customer accounts, and managing logistics.

Although computer-based information systems use computer technology to process raw data into meaningful information, there is a sharp distinction between a computer and a computer program on the one hand, and an information system on the other. Electronic computers and related software programs are the technical foundation, the tools and materials, of modern information systems. Computers provide the equipment for storing and processing information. Computer programs, or software, are sets of operating instructions that direct and control computer processing. Knowing how computers and computer programs work is important in designing solutions to organizational problems, but computers are only part of an information system.

|

Using a

handheld computer called a Delivery Information Acquisition Device

(DIAD), UPS drivers automatically capture customers’ signatures

along with pickup, delivery, and time-card information. UPS information

systems use these data to track packages while they are being transported. |

A house is an appropriate analogy. Houses are built with hammers, nails, and wood, but these do not make a house. The architecture, design, setting, landscaping, and all of the decisions that lead to the creation of these features are part of the house and are crucial for solving the problem of putting a roof over one’s head. Computers and programs are the hammer, nails, and lumber of CBIS, but alone they cannot produce the information a particular organization needs. To understand information systems, you must understand the problems they are designed to solve, their architectural and design elements, and the organizational processes that lead to these solutions.

|

|

It Isn’t Just Technology: A Business Perspective on Information Systems

Managers

and business firms invest in information technology and systems because

they provide real economic value to the business. The decision to build

or maintain an information system assumes that the returns on this investment

will be superior to other investments in buildings, machines, or other

assets. These superior returns will be expressed as increases in productivity,

as increases in revenues (which will increase the firm’s stock market

value), or perhaps as superior long-term strategic positioning of the

firm in certain markets (which produce superior revenues in the future).

There are

also situations in which firms invest in information systems to cope with

governmental regulations or other environmental demands. For instance,

one of the major ways firms can comply with the reporting requirements

of the recent Sarbanes-Oxley Act or the Health Insurance Portability and

Accountability Act (HIPAA) is to build a document management system that

can trace the flow of virtually all material documents it uses (see Chapter

12).

In some cases,

firms are required to invest in information systems simply because such

investments are required to stay in business. For instance, some small

banks may be forced to invest in automatic teller machine (ATM) networks

or offer complex banking services requiring large technology investments

simply because it is a “cost of doing business.” Nevertheless,

it is assumed that most information systems investments will be justified

by favorable returns.

We can see

that from a business perspective, an information system is an important

instrument for creating value for the firm. Information systems enable

the firm to increase its revenue or decrease its costs by providing information

that helps managers make better decisions or that improves the execution

of business processes. For example, the information system for analyzing

supermarket checkout data illustrated in Figure 1-5 can increase firm

profitability by helping managers make better decisions on which products

to stock and promote in retail supermarkets and as a result increase business

value.

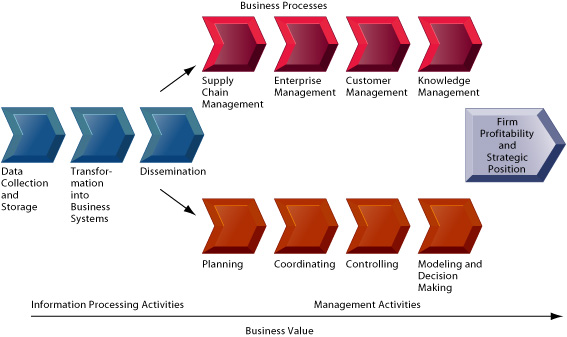

Every business

has an information value chain, illustrated in Figure 1-7, in which raw

information is systematically acquired and then transformed through various

stages that add value to that information. The value of an information

system to a business, as well as the decision to invest in any new information

system, is, in large part, determined by the extent to which the system

will lead to better management decisions, more efficient business processes,

and higher firm profitability. Although there are other reasons why systems

are built, their primary purpose is to contribute to corporate value.

|

FIGURE 1-7

The business information value chain

From a business perspective, information systems are part of a series of value-adding activities for acquiring, transforming, and distributing information that managers can use to improve decision making, enhance organizational performance, and, ultimately, increase firm profitability. |

The business perspective calls attention to the organizational and managerial nature of information systems. An information system represents an organizational and management solution, based on information technology, to a challenge posed by the environment. Every chapter in this book begins with short case study that illustrates this concept. A diagram at the beginning of each chapter illustrates the relationship between a changing business environment and resulting management and organizational decisions to use IT as a solution to challenges generated by the business environment.

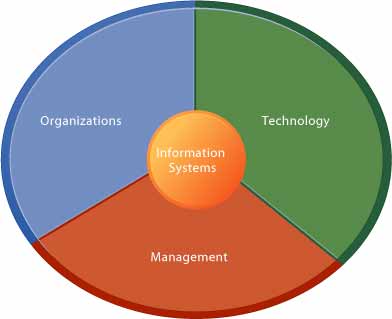

To fully understand information systems, a manager must understand the broader organization, management, and information technology dimensions of systems (see Figure 1-8) and their power to provide solutions to challenges and problems in the business environment. We refer to this broader understanding of information systems, which encompasses an understanding of the management and organizational dimensions of systems as well as the technical dimensions of systems, as information systems literacy. Information systems literacy includes a behavioral as well as a technical approach to studying information systems. Computer literacy, in contrast, focuses primarily on knowledge of information technology.

|

FIGURE 1-8

Information systems are more than computers

Using information systems effectively requires an understanding of the organization, management, and information technology shaping the systems. An information system creates value for the firm as an organizational and management solution to challenges posed by the environment. |

Review the diagram at the beginning of the chapter that reflects this expanded definition of an information system. The diagram shows how DaimlerChrysler’s production and supplier systems solve the business challenge presented by a fierce array of competitors and rapidly changing consumer preferences. These systems create value for DaimlerChrysler by making its production, supply chain, and quality control processes more efficient and cost effective. The diagram also illustrates how management, technology, and organizational elements work together to create the systems.

Each chapter of this text begins with a diagram similar to this one to help you analyze the chapter-opening case. You can use this diagram as a starting point for analyzing any information system or information system problem you encounter.

Dimensions of Information Systems

Let’s examine each of the dimensions of information systems—organizations, management, and information technology.

ORGANIZATIONS

Information systems are an integral part of organizations. Indeed, for some companies, such as credit reporting firms, without an information system, there would be no business. The key elements of an organization are its people, structure, business processes, politics, and culture. We introduce these components of organizations here and describe them in greater detail in Chapters 2 and 3.

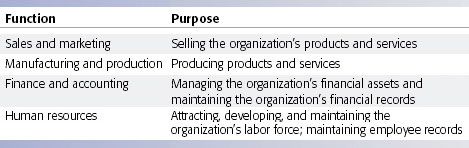

Organizations are composed of different levels and specialties. Their structures reveal a clear-cut division of labor. Experts are employed and trained for different functions. The major business functions, or specialized tasks performed by business organizations, consist of sales and marketing, manufacturing and production, finance and accounting, and human resources (see Table 1-2).

| TABLE 1-2 Major Business Functions  |

Chapter 2 provides more detail on these business functions and the ways

in which they are supported by information systems. Each chapter of this

text concludes with a Make IT Your Business section showing how chapter

topics relate to each of these functional areas. The section also provides

page numbers in each chapter where these functional examples can be found.

An organization

coordinates work through a structured hierarchy and through its business

processes, which we defined earlier. The hierarchy arranges people in

a pyramid structure of rising authority and responsibility. The upper

levels of the hierarchy consist of managerial, professional, and technical

employees, whereas the lower levels consist of operational personnel.

Most organizations’ business processes include formal rules

that have been developed over a long time for accomplishing tasks. These

rules guide employees in a variety of procedures, from writing an invoice

to responding to customer complaints. Some of these procedures have been

formalized and written down, but others are informal work practices, such

as a requirement to return telephone calls from coworkers or customers,

that are not formally documented. Many business processes are incorporated

into information systems, such as how to pay a supplier or how to correct

an erroneous bill.

Organizations require many different kinds of skills and people.

In addition to managers, knowledge workers (such as engineers, architects,

or scientists) design products or services and create new knowledge, and

data workers (such as secretaries, bookkeepers, or clerks) process the

organization’s paperwork. Production or service workers (such as

machinists, assemblers, or packers) actually produce the organization’s

products or services.

Each organization has a unique culture, or fundamental set of assumptions,

values, and ways of doing things, that has been accepted by most of its

members. Parts of an organization’s culture can always be found

embedded in its information systems. For instance, the United Parcel Service’s

concern with placing service to the customer first is an aspect of its

organizational culture that can be found in the company’s package

tracking systems.

Different levels and specialties in an organization create different interests and points of view. These views often conflict. Conflict is the basis for organizational politics. Information systems come out of this cauldron of differing perspectives, conflicts, compromises, and agreements that are a natural part of all organizations. In Chapter 3 we examine these features of organizations and their role in the development of information systems in greater detail.

MANAGEMENT

Management’s job is to make sense out of the many situations faced by organizations, make decisions, and formulate action plans to solve organizational problems. Managers perceive business challenges in the environment; they set the organizational strategy for responding to those challenges; and they allocate the human and financial resources to coordinate the work and achieve success. Throughout, they must exercise responsible leadership. The business information systems described in this book reflect the hopes, dreams, and realities of real-world managers.But managers must do more than manage what already exists. They must also create new products and services and even re-create the organization from time to time. A substantial part of management responsibility is creative work driven by new knowledge and information. Information technology can play a powerful role in redirecting and redesigning the organization. Chapter 3 describes managerial activities, and Chapter 13 treats management decision making in detail.

It is important to note that managerial roles and decisions vary at different levels of the organization. Senior managers make long-range strategic decisions about what products and services to produce. Middle managers carry out the programs and plans of senior management. Operational managers are responsible for monitoring the firm’s daily activities. All levels of management are expected to be creative, to develop novel solutions to a broad range of problems. Each level of management has different information needs and information system requirements.

TECHNOLOGY

Information technology is one of many tools managers use to cope with change. Computer hardware is the physical equipment used for input, processing, and output activities in an information system. It consists of the following: the computer processing unit; various input, output, and storage devices; and physical media to link these devices together.Computer software consists of the detailed, preprogrammed instructions that control and coordinate the computer hardware components in an information system. Chapter 6 describes the contemporary software and hardware platforms used by firms today in greater detail.

Storage technology includes both the physical media for storing data, such as magnetic disk, optical disc, or tape, and the software governing the organization of data on these physical media. More detail on data organization and access methods can be found in Chapter 7.

Communications technology, consisting of both physical devices and software, links the various pieces of hardware and transfers data from one physical location to another. Computers and communications equipment can be connected in networks for sharing voice, data, images, sound, or even video. A network links two or more computers to share data or resources such as a printer.

The world’s largest and most widely used network is the Internet. The Internet is an international network of networks that are both commercial and publicly owned. The Internet connects hundreds of thousands of different networks from more than 200 countries around the world. More than 900 million people working in science, education, government, and business use the Internet to exchange information or business transactions with other organizations around the globe. Chapter 8 provides more detail on networks and Internet technology.

The Internet is extremely elastic. If networks are added or removed, or if failures occur in parts of the system, the rest of the Internet continues to operate. Through special communication and technology standards, any computer can communicate with virtually any other computer linked to the Internet using ordinary telephone lines.

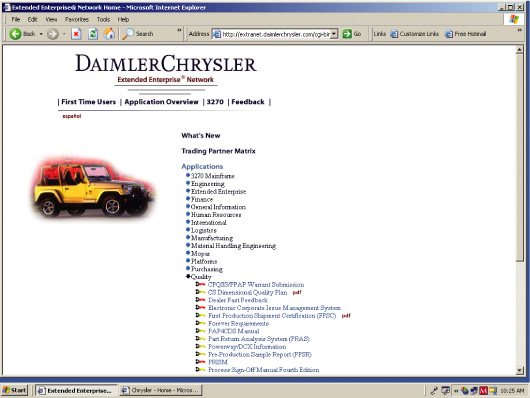

The Internet has created a new “universal” technology platform on which to build all sorts of new products, services, strategies, and business models. This same technology platform has internal uses, providing the connectivity to link different systems and networks within the firm. Internal corporate networks based on Internet technology are called intranets. Private intranets extended to authorized users outside the organization are called extranets, and firms use such networks to coordinate their activities with other firms for making purchases, collaborating on design, and other interorganizational work. Some of DaimlerChrysler’s systems for coordinating with suppliers are based on extranets.

Because it offers so many new possibilities for doing business, the Internet service known as the World Wide Web is of special interest to organizations and managers. The World Wide Web is a system with universally accepted standards for storing, retrieving, formatting, and displaying information in a networked environment. Information is stored and displayed as electronic “pages” that can contain text, graphics, animations, sound, and video. These Web pages can be linked electronically to other Web pages, regardless of where they are located, and viewed by any type of computer. By clicking on highlighted words or buttons on a Web page, you can link to related pages to find additional information, software programs, or still more links to other points on the Web. The Web can serve as the foundation for new kinds of information systems such as UPS’s Web-based package tracking system or Cemex’s Web system for entering customer orders and checking shipments described in this chapter’s Window on Organizations.

All of the Web pages maintained by an organization or individual are called a Web site. Businesses have created Web sites with stylish typography, colorful graphics, push-button interactivity, and sound and video to disseminate product information widely, to “broadcast” advertising and messages to customers, to collect electronic orders and customer data, and, increasingly, to coordinate far-flung sales forces and organizations on a global scale.

|

DaimlerChrysler’s

Extended Enterprise Network is an extranet for suppliers to access

a series of internal company applications. Internet technology standards

make it possible for DaimlerChrysler to link to the systems of many

different companies. |

In Chapters 4 and 8 we describe the Web and other Internet capabilities in greater detail. We also discuss relevant features of Internet technology throughout the text because it affects so many aspects of information systems in organizations.

All of these technologies represent resources that can be shared throughout the organization and constitute the firm’s information technology (IT) infrastructure. The IT infrastructure provides the foundation, or platform, on which the firm can build its specific information systems. Each organization must carefully design and manage its information technology infrastructure so that it has the set of technology services it needs for the work it wants to accomplish with information systems. Chapters 6 through 10 of this text examine each major technology component of information technology infrastructure and show how they all work together to create the technology platform for the organization.

Let’s look at the case about UPS’s package tracking system in the Window on Technology and identify the organization, management, and technology elements. The organization element anchors the package tracking system in UPS’s sales and production functions (the main product of UPS is a service—package delivery). It specifies the required procedures for identifying packages with both sender and recipient information, taking inventory, tracking the packages en route, and providing package status reports for UPS customers and customer service representatives. The system must also provide information to satisfy the needs of managers and workers. UPS drivers need to be trained in both package pickup and delivery procedures and in how to use the package tracking system so that they can work efficiently and effectively. UPS customers may need some training to use UPS in-house package tracking software or the UPS Web site.

UPS’s management is responsible for monitoring service levels and costs and for promoting the company’s strategy of combining low-cost and superior service. Management decided to use automation to increase the ease of sending a package using UPS and of checking its delivery status, thereby reducing delivery costs and increasing sales revenues.

The technology supporting this system consists of handheld computers, bar-code scanners, wired and wireless communications networks, desktop computers, UPS’s central computer, storage technology for the package delivery data, UPS in-house package tracking software, and software to access the World Wide Web. The result is an information system solution to the business challenge of providing a high level of service with low prices in the face of mounting competition.

Internet Connection The Internet Connection for this chapter will take you to the United Parcel Service Web site where you can complete an exercise to evaluate how UPS uses the Web and other information technology in its daily operations.

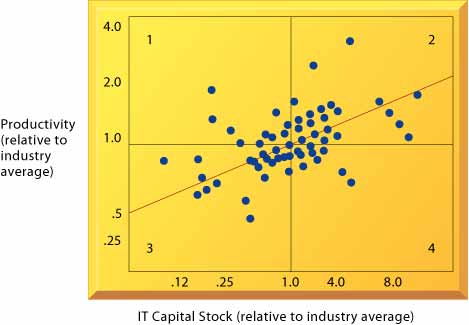

COMPLEMENTARY ASSETS AND ORGANIZATIONAL

CAPITAL

Awareness of the organizational and managerial dimensions of information

systems can help us understand why some firms achieve better results from

their information systems than others. Studies of returns from information

technology investments show that there is considerable variation in the

returns firms receive (see Figure 1-9). Some firms invest a great deal

and receive a great deal (quadrant 2); others invest an equal amount and

receive few returns (quadrant 4). Still other firms invest little and

receive much (quadrant 1), whereas others invest little and receive little

(quadrant 3). This suggests that investing in information technology does

not by itself guarantee good returns. What accounts for this variation

among firms?

|

FIGURE 1-9 Variation

in returns on information technology investment Although, on average, investments in information technology produce returns far above those returned by other investments, there is considerable variation across firms. Source: Based on Brynjolfsson and Hitt (2000). |

The answer lies in the concept of complementary assets. Information

technology investments alone cannot make organizations and managers more

effective unless they are accompanied by supportive values, structures,

and behavior patterns in the organization and other complementary assets.

Complementary assets are those assets required to derive value from a

primary investment (Teece, 1998). For instance, to realize value from

automobiles requires substantial complementary investments in highways,

roads, gasoline stations, repair facilities, and a legal regulatory structure

to set standards and control drivers.

Recent research on business information technology investment indicates

that firms that support their technology investments with investments

in complementary assets, such as new business processes, management behavior,

organizational culture, or training, receive superior returns, whereas

those firms failing to make these complementary investments receive less

or no returns on their information technology investments (Brynjolfsson,

2003; Brynjolfsson and Hitt, 2000; Davern and Kauffman, 2000; Laudon,

1974; Marchand, 2004). These investments in organization and management

are also known as organizational and management capital.

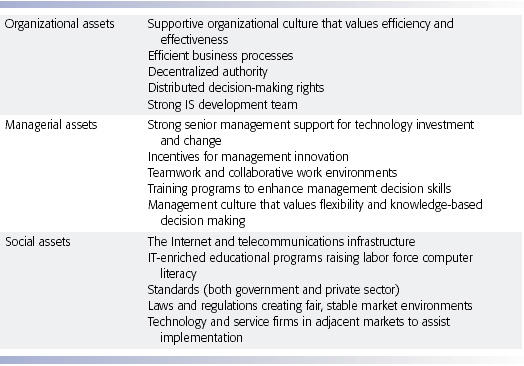

Table 1-3 lists the major complementary investments that firms

need to make to realize value from their information technology investments.

Some of this investment involves tangible assets, such as buildings, machinery,

and tools. However, the value of investments in information technology

depends to a large extent on complementary investments in management and

organization.

| TABLE 1-3 Complementary Social, Managerial, and Organizational Assets Required to Optimize Returns from Information Technology Investments  |

Key organizational complementary investments are a supportive business culture that values efficiency and effectiveness, efficient business processes, decentralization of authority, highly distributed decision rights, and a strong information system (IS) development team.

Important managerial complementary assets are strong senior management support for change, incentive systems that monitor and reward individual innovation, an emphasis on teamwork and collaboration, training programs, and a management culture that values flexibility and knowledge.

Important social investments (not made by the firm but by the society at large, other firms, governments, and other key market actors) are the Internet and the supporting Internet culture, educational systems, network and computing standards, regulations and laws, and the presence of technology and service firms.

Throughout the book we emphasize a framework of analysis that considers technology, management, and organizational assets and their interactions. Perhaps the single most important theme in the book, reflected in case studies, vignettes, and exercises, is that managers need to consider the broader organization and management dimensions of information systems to understand current problems as well as to derive substantial above-average returns from their information technology investments. As you will see throughout the text, firms that can address these related dimensions of the IT investment are, on average, richly rewarded.