| Section 16.2: Full Text |

Chapter

Contents | View Full Text | View

Bullet Text |

| Global Strategies and Business Organization |

| Global Systems to Fit the Strategy |

| Reorganizing the Business |

ORGANIZING INTERNATIONAL INFORMATION SYSTEMS

Three organizational issues face corporations seeking a global position: choosing a strategy,

organizing the business, and organizing the systems management area. The first two

are closely connected, so we discuss them together.

Global Strategies and Business Organization

Four main global strategies form the basis for global firms’ organizational structure.

These are domestic exporter, multinational, franchiser, and transnational. Each of these

strategies is pursued with a specific business organizational structure (see Table 16-3). For

simplicity’s sake, we describe three kinds of organizational structure or governance: centralized

(in the home country), decentralized (to local foreign units), and coordinated (all units participate as equals). Other types of governance patterns can be observed in specific

companies (e.g., authoritarian dominance by one unit, a confederacy of equals, a federal

structure balancing power among strategic units, and so forth; see Keen, 1991).

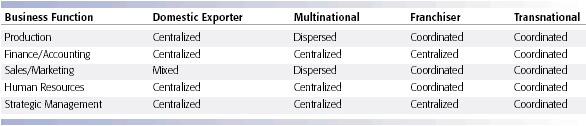

TABLE 16-3 Global Business Strategy and Structure  |

The domestic exporter strategy is characterized by heavy centralization of corporate activities in the home country of origin. Nearly all international companies begin this way, and some move on to other forms. Production, finance/accounting, sales/marketing, human resources, and strategic management are set up to optimize resources in the home country. International sales are sometimes dispersed using agency agreements or subsidiaries, but even here foreign marketing is totally reliant on the domestic home base for marketing themes and strategies. Caterpillar Corporation and other heavy capital-equipment manufacturers fall into this category of firm.

The multinational strategy concentrates financial management and control out of a central home base while decentralizing production, sales, and marketing operations to units in other countries. The products and services on sale in different countries are adapted to suit local market conditions. The organization becomes a far-flung confederation of production and marketing facilities in different countries. Many financial service firms, along with a host of manufacturers, such as General Motors, Chrysler, and Intel, fit this pattern.

Franchisers are an interesting mix of old and new. On the one hand, the product is created, designed, financed, and initially produced in the home country, but for product-specific reasons must rely heavily on foreign personnel for further production, marketing, and human resources. Food franchisers such as McDonald’s, Mrs. Fields Cookies, and KFC fit this pattern. McDonald’s created a new form of fast-food chain in the United States and continues to rely largely on the United States for inspiration of new products, strategic management, and financing. Nevertheless, because the product must be produced locally—it is perishable—extensive coordination and dispersal of production, local marketing, and local recruitment of personnel are required.

Generally, foreign franchisees are clones of the mother country units, but fully coordinated worldwide production that could optimize factors of production is not possible. For instance, potatoes and beef can generally not be bought where they are cheapest on world markets but must be produced reasonably close to the area of consumption.

Transnational firms are the stateless, truly globally managed firms that may represent a larger part of international business in the future. Transnational firms have no single national headquarters but instead have many regional headquarters and perhaps a world headquarters. In a transnational strategy, nearly all the value-adding activities are managed from a global perspective without reference to national borders, optimizing sources of supply and demand wherever they appear, and taking advantage of any local competitive advantages. Transnational firms take the globe, not the home country, as their management frame of reference. The governance of these firms has been likened to a federal structure in which there is a strong central management core of decision making, but considerable dispersal of power and financial muscle throughout the global divisions. Few companies have actually attained transnational status, but Citicorp, Sony, Ford, and others are attempting this transition.

Information technology and improvements in global telecommunications are giving international firms more flexibility to shape their global strategies. Protectionism and a need to serve local markets better encourage companies to disperse production facilities and at least become multinational. At the same time, the drive to achieve economies of scale across national boundaries moves transnationals toward a global management perspective and a concentration of power and authority. Hence, there are forces of decentralization and dispersal, as well as forces of centralization and global coordination.

Global Systems to Fit the Strategy

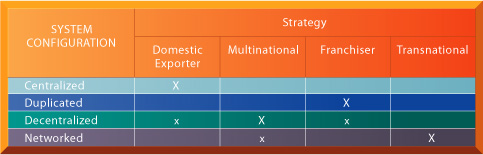

Information technology and improvements in global telecommunications are giving international firms more flexibility to shape their global strategies. The configuration, management, and development of systems tend to follow the global strategy chosen (Roche, 1992; Ives and Jarvenpaa, 1991). Figure 16-3 depicts the typical arrangements.

|

FIGURE 16-3 Global strategy and systems configurations

The large Xs show the dominant

patterns, and the small Xs show

the emerging patterns. For

instance, domestic exporters rely

predominantly on centralized systems,

but there is continual pressure

and some development of

decentralized systems in local

marketing regions.

By systems we mean the full range of activities involved in building information systems: conception and alignment with the strategic business plan, systems development, and ongoing operation. For the sake of simplicity, we consider four types of systems configuration. Centralized systems are those in which systems development and operation occur totally at the domestic home base. Duplicated systems are those in which development occurs at the home base but operations are handed over to autonomous units in foreign locations. Decentralized systems are those in which each foreign unit designs its own unique solutions and systems. Networked systems are those in which systems development and operations occur in an integrated and coordinated fashion across all units.

As can be seen in Figure 16-3, domestic exporters tend to have highly centralized systems in which a single domestic systems development staff develops worldwide applications. Multinationals offer a direct and striking contrast: Here, foreign units devise their own systems solutions based on local needs with few if any applications in common with headquarters (the exceptions being financial reporting and some telecommunications applications). Franchisers have the simplest systems structure: Like the products they sell, franchisers develop a single system usually at the home base and then replicate it around the world. Each unit, no matter where it is located, has identical applications. Last, the most ambitious form of systems development is found in the transnational: Networked systems are those in which there is a solid, singular global environment for developing and operating systems. This usually presupposes a powerful telecommunications backbone, a culture of shared applications development, and a shared management culture that crosses cultural barriers. The networked systems structure is the most visible in financial services where the homogeneity of the product—money and money instruments— seems to overcome cultural barriers.

Reorganizing the Business

How should a firm organize itself for doing business on an international scale? To develop a global company and information systems support structure, a firm needs to follow these principles:

Organize value-adding activities along lines of comparative advantage. For instance, marketing/sales functions should be located where they can best be performed, for least cost and maximum impact; likewise with production, finance, human resources, and information systems.

Develop and operate systems units at each level of corporate activity—regional, national, and international. To serve local needs, there should be host country systems units of some magnitude. Regional systems units should handle telecommunications and systems development across national boundaries that take place within major geographic regions (European, Asian, American). Transnational systems units should be established to create the linkages across major regional areas and coordinate the development and operation of international telecommunications and systems development (Roche, 1992).

Establish at world headquarters a single office responsible for development of international systems, a global chief information officer (CIO) position.

Many successful companies have devised organizational systems structures along these principles. The success of these companies relies not only on the proper organization of activities, but also on a key ingredient—a management team that can understand the risks and benefits of international systems and that can devise strategies for overcoming the risks. We turn to these management topics next.