| Section 2.3: Full Text |

Chapter

Contents | View Full Text | View

Bullet Text

|

| Business Processes and Information Systems | |

| Systems for Enterprise-Wide Process Integration | |

| Overview of Enterprise Applications | |

| Window on Technology | |

INTEGRATING FUNCTIONS AND BUSINESS PROCESSES:

INTRODUCTION TO ENTERPRISE APPLICATIONS

One of the major challenges facing firms today is putting together data

from the systems we have just described to make information flow across

the enterprise. Electronic commerce, electronic business, and intensifying

global competition are forcing firms to focus on speed to market, improving

customer service, and more efficient execution. The flow of information

and work needs to be orchestrated so that the organization can perform

like a well-oiled machine. These changes require powerful new systems

that can integrate information from many different functional areas and

organizational units and coordinate firm activities with those of suppliers

and other business partners.

Business Processes and Information Systems

The new digital firm business environment requires companies to think more strategically about their business processes, which we introduced in Chapter 1. Business processes refer to sets of logically related activities for accomplishing a specific business result. Business processes also refer to the unique ways in which organizations and management coordinate these activities. A company’s business processes can be a source of competitive strength if they enable the company to innovate better or to execute better than its rivals. Business processes can also be liabilities if they are based on outdated ways of working that impede organizational responsiveness and efficiency.

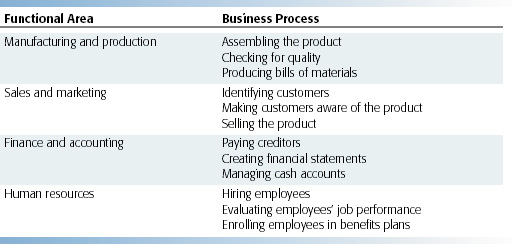

Some business processes support the major functional areas of the firm, others are cross-functional. Table 2-6 describes some typical business processes for each of the functional areas.

|

TABLE 2-6 Examples of Functional Business Processes  |

Many business processes are cross-functional, transcending the boundaries between sales, marketing, manufacturing, and research and development. These cross-functional processes cut across the traditional organizational structure, grouping employees from different functional specialties to complete a piece of work. For example, the order fulfillment process at many companies requires cooperation among the sales function (receiving the order, entering the order), the accounting function (credit checking and billing for the order), and the manufacturing function (assembling and shipping the order). Figure 2-12 illustrates how this cross-functional process might work. Information systems support these cross-functional processes as well as processes for the separate business functions.

|

| FIGURE 2-12 The order fulfillment process Generating and fulfilling an order is a multistep process involving activities performed by the sales, manufacturing and production, and accounting functions. |

Systems for Enterprise-Wide Process Integration

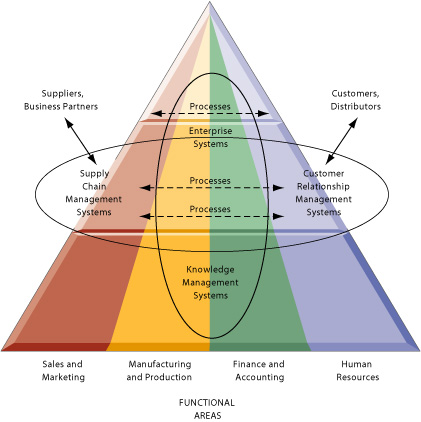

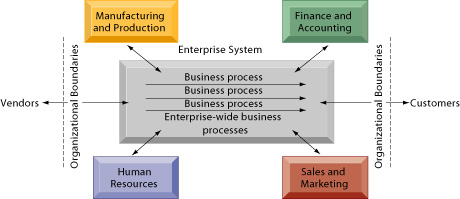

Today’s firms are finding that they can become more flexible and productive by coordinating their business processes more closely and, in some cases, integrating these processes so they focus on efficient management of resources and customer service. Enterprise applications are designed to support organization-wide process coordination and integration. These enterprise applications consist of enterprise systems, supply chain management systems, customer relationship management systems, and knowledge management systems. Each of these enterprise applications integrates a related set of functions and business processes to enhance the performance of the organization as a whole.Generally, these more contemporary systems take advantage of corporate intranets and Web technologies that enable the efficient transfer of information within the firm and to partner firms. These systems are inherently cross-level, cross-functional, and business process oriented. Figure 2-13 shows that the architecture for these enterprise applications encompasses processes spanning the entire organization and, in some cases, extending beyond the organization to customers, suppliers, and other key business partners.

|

Enterprise systems create an integrated organization-wide platform to coordinate key internal processes of the firm. Information systems for supply chain management (SCM) and customer relationship management (CRM) help coordinate processes for managing the firm’s relationship with its suppliers and customers. Knowledge management systems enable organizations to better manage processes for capturing and applying knowledge and expertise. Collectively, these four systems represent the areas in which corporations are digitally integrating their information flows and making major information system investments.

Overview of Enterprise Applications

Let’s look briefly at each of the major enterprise applications to see how they fit into the overall information architecture of the enterprise. We examine enterprise systems and systems for supply chain management and customer relationship management in greater detail in Chapter 11 and cover knowledge management applications in Chapter 12.

OVERVIEW OF ENTERPRISE SYSTEMS

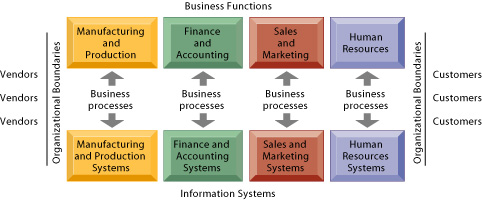

A large organization typically has many

different kinds of information systems that support different functions,

organizational levels, and business processes. Most of these systems were

built around different functions, business units, and business processes

that do not “talk” to each other and thus cannot automatically

exchange information. Managers might have a hard time assembling the data

they need for a comprehensive, overall picture of the organization’s

operations. For instance, sales personnel might not be able to tell at

the time they place an order whether the items that were ordered were

in inventory; customers could not track their orders; and manufacturing

could not communicate easily with finance to plan for new production.

This fragmentation of data in hundreds of separate systems could thus

have a negative impact on organizational efficiency and business performance.

Figure 2-14 illustrates the traditional arrangement of information systems.

|

Enterprise

systems, also known as enterprise resource planning (ERP) systems solve

this problem by providing a single information system for organization-wide

coordination and integration of key business processes. Information that

was previously fragmented in different systems can seamlessly flow throughout

the firm so that it can be shared by business processes in manufacturing,

accounting, human resources, and other areas. Discrete business processes

from sales, production, finance, and logistics can be integrated into

company-wide business processes that flow across organizational levels

and functions. Figure 2-15 illustrates how enterprise systems work.

|

|

The enterprise system collects data from various key business processes in manufacturing and production, finance and accounting, sales and marketing, and human resources and stores the data in a single comprehensive data repository where they can be used by other parts of the business. Managers emerge with more precise and timely information for coordinating the daily operations of the business and a firmwide view of business processes and information flows.

For

instance, when a sales representative in Brussels enters a customer order,

the data flow automatically to others in the company who need to see them.

The factory in Hong Kong receives the order and begins production. The

warehouse checks its progress online and schedules the shipment date.

The warehouse can check its stock of parts and replenish whatever the

factory has depleted. The enterprise system stores production information,

where it can be accessed by customer service representatives to track

the progress of the order through every step of the manufacturing process.

Updated sales and production data automatically flow to the accounting

department. The system transmits information for calculating the salesperson’s

commision to the payroll department. The system also automatically recalculates

the company’s balance sheets, accounts receivable and payable ledgers,

cost-center accounts, and available cash. Corporate headquarters in London

can view up-to-the-minute data on sales, inventory, and production at

every step of the process, as well as updated sales and production forecasts

and calculations of product cost and availability. Chapter 11 provides

more detail on enterprise system capabilities.

OVERVIEW OF SUPPLY CHAIN MANAGEMENT SYSTEMS

Supply chain management (SCM) systems are more outward facing, focusing

on helping the firm manage its relationship with suppliers to optimize

the planning, sourcing, manufacturing, and delivery of products and services.

These systems provide information to help suppliers, purchasing firms,

distributors, and logistics companies coordinate, schedule, and control

business processes for procurement, production, inventory management,

and delivery of products and services.

Supply chain management systems are one type of interorganizational system because they automate the flow of information across organizational boundaries. A firm using a supply chain management system would exchange information with its suppliers about availability of materials and components, delivery dates for shipments of supplies, and production requirements. It might also use the system to exchange information with its distributors about inventory levels, the status of orders being fulfilled, or delivery dates for shipments of finished goods. You will find examples of other types of interorganizational information systems throughout this text because such systems make it possible for firms to link electronically to customers and to outsource their work to other companies.

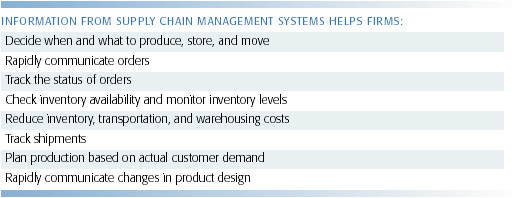

Table 2-7 describes how firms can benefit from supply chain management systems. The ultimate objective is to get the right amount of their products from their source to their point of consumption with the least amount of time and with the lowest cost. Supply chain management systems can be built using intranets, extranets, or special supply chain management software.

TABLE 2-7 How Information Systems Facilitate Supply Chain Management  |

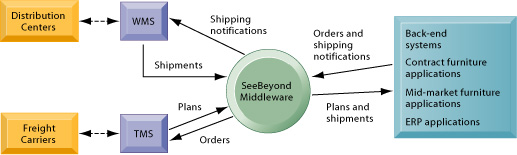

Figure

2-16 illustrates the supply chain management systems used by Haworth,

a world-leading manufacturer and designer of office furniture described

in the Window on Technology. Haworth needed to synchronize manufacturing

and distribution activities to cut costs and boost efficiency by having

material flow continuously from multiple manufacturing centers to multiple

distribution centers. It implemented new systems for warehouse management

and transportation management. These systems enable Haworth to deliver

multipart shipments requiring assembly in the correct sequence, accommodate

shipping volumes that can vary by a factor of 10 from one day to the next,

and handle last-minute changes in customer orders.

|

|

OVERVIEW OF CUSTOMER RELATIONSHIP MANAGEMENT SYSTEMS

Instead of treating customers as exploitable sources of income, businesses are now viewing them as long-term assets to be nurtured through customer relationship management. Customer relationship management (CRM) systems focus on coordinating all of the business processes surrounding the firm’s interactions with its customers in sales, marketing, and service to optimize revenue, customer satisfaction, and customer retention. The ideal CRM system provides end-to-end customer care from receipt of an order through product delivery.

In

the past, a firm’s processes for sales, service, and marketing were

highly compartmentalized, and these departments did not share much essential

customer information. Some information on a specific customer might be

stored and organized in terms of that person’s account with the

company. Other pieces of information about the same customer might be

organized by products that were purchased. There was no way to consolidate

all of this information to provide a unified view of a customer across

the company. CRM systems try to solve this problem by integrating the

firm’s customer-related processes and consolidating customer information

from multiple communication channels— telephone, e-mail, wireless

devices, or the Web—so that the firm can present one coherent face

to the customer (see Figure 2-17).

|

Good CRM systems provide data and analytical tools for answering questions such as these: What is the value of a particular customer to the firm over his or her lifetime? Who are our most loyal customers? (It can cost six times more to sell to a new customer than to an existing customer.) Who are our most profitable customers? What do these profitable customers want to buy? Firms can then use the answers to these questions to acquire new customers, provide better service and support to existing customers, customize their offerings more precisely to customer preferences, and provide ongoing value to retain profitable customers.

OVERVIEW OF KNOWLEDGE MANAGEMENT SYSTEMSThe value of a firm’s products and

services is based not only on its physical resources but also on intangible

knowledge assets. Some firms perform better than others because they have

better knowledge about how to create, produce, and deliver products and

services. This firm knowledge is difficult to imitate, unique, and can

be leveraged into long-term strategic benefit. Knowledge management systems

collect all relevant knowledge and experience in the firm and make it

available wherever and whenever it is needed to support business processes

and management decisions. They also link the firm to external sources

of knowledge.

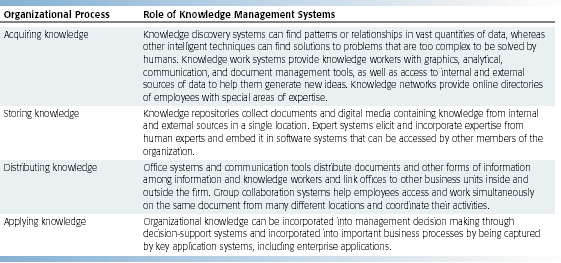

Knowledge

management systems support processes for acquiring, storing, distributing,

and applying knowledge, as well as processes for creating new knowledge

and integrating it into the organization. They include enterprise-wide

systems for managing and distributing documents, graphics, and other digital

knowledge objects, systems for creating corporate knowledge directories

of employees with special areas of expertise, office systems for distributing

knowledge and information, and knowledge work systems to facilitate knowledge

creation. Other knowledge management applications are expert systems that

codify the knowledge of experts in information systems that can be used

by other members of the organization and tools for knowledge discovery

that recognize patterns and important relationships in large pools of

data. Table 2-8 provides examples of knowledge management systems, and

Chapter 12 describes these knowledge management applications in detail.

TABLE 2-8 Knowledge Management Systems in the Organization  |