| Section 5.1: Full Text |

Chapter

Contents | View Full Text | View

Bullet Text

|

| A Model for Thinking About Ethical, Social, and Political Issues |

| Five Moral Dimensions of the Information Age |

| Key Technology Trends That Raise Ethical Issues |

ChoicePoint uses information systems to create a background checking service that is very valuable for businesses and even for job applicants. It provides users with access to massive pools of data about individuals, including their credit history and driving records. But ChoicePoint’s service could also be abused by making it easier to find out detailed information about other people that users are not entitled to see.

ChoicePoint’s case shows that information systems raise new and often perplexing ethical challenges. You’ll want to know what these ethical challenges are and how you should deal with them as a manager and as an individual. This chapter helps you by describing the major ethical and social issues raised by information systems and by providing guidelines for analyzing ethical issues on your own.

UNDERSTANDING ETHICAL AND SOCIAL ISSUES RELATED TO SYSTEMS

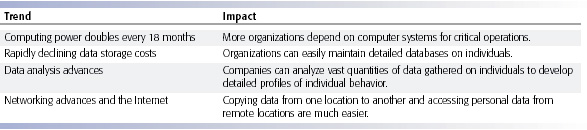

In the last five years we have witnessed arguably one of

the most ethically challenging periods for U.S. and global business. Table

5-1 provides a small sample of cases demonstrating failed ethical judgment

by senior and middle managers in the past few years. These lapses in management

ethical and business judgment occurred across a broad spectrum of industries.

TABLE 5-1 Recent Examples

of Failed Ethical Judgment by Managers |

In today’s

new legal environment, managers who violate the law and are convicted

will most likely spend time in prison. United States Federal Sentencing

Guidelines adopted in 1987 mandate that federal judges impose stiff sentences

on business executives based on the monetary value of the crime, the presence

of a conspiracy to prevent discovery of the crime, the use of structured

financial transactions to hide the crime, and failure to cooperate with

prosecutors (U.S. Sentencing Commission, 2004).

Although

in the past business firms would often pay for the legal defense of their

employees enmeshed in civil charges and criminal investigations, now firms

are encouraged to cooperate with prosecutors to reduce charges against

the entire firm for obstructing investigations. These developments mean

that, more than ever, managers and employees will have to judge for themselves

what constitutes proper legal and ethical conduct.

Although

these major instances of failed ethical and legal judgment were not master-minded

by information systems departments, financial reporting information systems

were instrumental in many of these frauds. In many cases, the perpetrators

of these crimes artfully used financial reporting information systems

to bury their decisions from public scrutiny in the vain hope they would

never be caught. We deal with the issue of control in financial reporting

and other information systems in Chapter 10. In this chapter we talk about

the ethical dimensions of these and other actions based on the use of

information systems.

Ethics refers to the principles of right and wrong that individuals, acting

as free moral agents, use to make choices to guide their behaviors. Information

systems raise new ethical questions for both individuals and societies

because they create opportunities for intense social change, and thus

threaten existing distributions of power, money, rights, and obligations.

Like other technologies, such as steam engines, electricity, telephone,

and radio, information technology can be used to achieve social progress,

but it can also be used to commit crimes and threaten cherished social

values. The development of information technology will produce benefits

for many and costs for others.

Ethical issues in information systems have been given new urgency by the

rise of the Internet and electronic commerce. Internet and digital firm

technologies make it easier than ever to assemble, integrate, and distribute

information, unleashing new concerns about the appropriate use of customer

information, the protection of personal privacy, and the protection of

intellectual property.

Other pressing ethical issues raised by information systems include

establishing accountability for the consequences of information systems,

setting standards to safeguard system quality that protect the safety

of the individual and society, and preserving values and institutions

considered essential to the quality of life in an information society.

When using information systems, it is essential to ask, What is the ethical

and socially responsible course of action?

A Model for Thinking About Ethical,

Social, and Political Issues

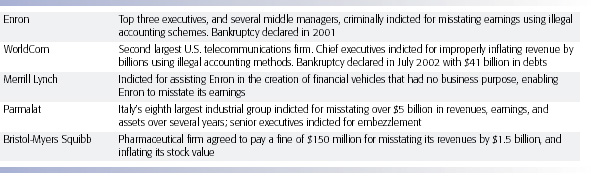

Ethical, social, and political issues are closely linked. The ethical dilemma you may face as a manager of information systems typically is reflected in social and political debate. One way to think about these relationships is given in Figure 5-1. Imagine society as a more or less calm pond on a summer day, a delicate ecosystem in partial equilibrium with individuals and with social and political institutions. Individuals know how to act in this pond because social institutions (family, education, organizations) have developed well-honed rules of behavior, and these are backed by laws developed in the political sector that prescribe behavior and promise sanctions for violations. Now toss a rock into the center of the pond. But imagine instead of a rock that the disturbing force is a powerful shock of new information technology and systems hitting a society more or less at rest. What happens? Ripples, of course.

|

|

FIGURE 5-1 The relationship between ethical, social, and political issues in an information society The introduction of new information technology has a ripple effect, raising new ethical, social, and political issues that must be dealt with on the individual, social, and political levels. These issues have five moral dimensions: information rights and obligations, property rights and obligations, system quality, quality of life, and accountability and control. |

Suddenly individual actors are confronted with new situations often not covered by the old rules. Social institutions cannot respond overnight to these ripples—it may take years to develop etiquette, expectations, social responsibility, politically correct attitudes, or approved rules. Political institutions also require time before developing new laws and often require the demonstration of real harm before they act. In the meantime, you may have to act. You may be forced to act in a legal gray area.

We can use this model to illustrate the dynamics that connect ethical, social, and political issues. This model is also useful for identifying the main moral dimensions of the information society, which cut across various levels of action—individual, social, and political.

Five Moral Dimensions of the Information Age

The major ethical, social, and political issues raised by information systems include the following moral dimensions:

|

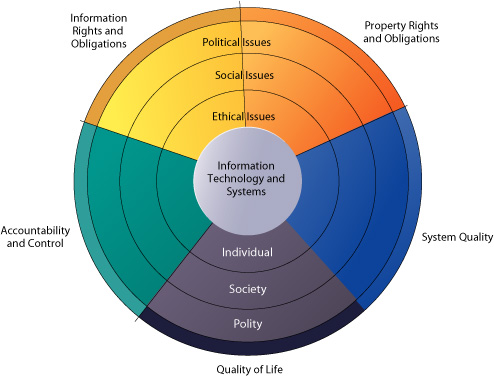

Key Technology Trends That Raise Ethical Issues

Ethical issues long preceded information technology. Nevertheless, information technology has heightened ethical concerns, taxed existing social arrangements, and made some laws obsolete or severely crippled. There are four key technological trends responsible for these ethical stresses and they are summarized in Table 5-2.

|

Advances in data storage techniques and rapidly declining storage costs have been responsible for the multiplying databases on individuals—employees, customers, and potential customers—maintained by private and public organizations. These advances in data storage have made the routine violation of individual privacy both cheap and effective. Already massive data storage systems are cheap enough for regional and even local retailing firms to use in identifying customers.

Advances in data analysis techniques for large pools of data are a third technological trend that heightens ethical concerns because companies and government agencies are able to find out much detailed personal information about individuals. With contemporary data management tools (see Chapter 7) companies can assemble and combine the myriad pieces of information about you stored on computers much more easily than in the past.

Think of all the ways you generate computer information about yourself—credit card purchases, telephone calls, magazine subscriptions, video rentals, mail-order purchases, banking records, and local, state, and federal government records (including court and police records). Put together and mined properly, this information could reveal not only your credit information but also your driving habits, your tastes, your associations, and your political interests.

Companies with products to sell purchase relevant information from these sources to help them more finely target their marketing campaigns. Chapters 3 and 7 describe how companies can analyze large pools of data from multiple sources to rapidly identify buying patterns of customers and suggest individual responses. The use of computers to combine data from multiple sources and create electronic dossiers of detailed information on individuals is called profiling.

For example, hundreds of Web sites allow DoubleClick (www.doubleclick.net), an Internet advertising broker, to track the activities of their visitors in exchange for revenue from advertisements based on visitor information DoubleClick gathers. DoubleClick uses this information to create a profile of each online visitor, adding more detail to the profile as the visitor accesses an associated DoubleClick site. Over time, DoubleClick can create a detailed dossier of a person’s spending and computing habits on the Web that can be sold to companies to help them target their Web ads more precisely.

|

| Credit card purchases can make personal information available to market researchers, telemarketers, and direct mail companies. Advances in information technology facilitate the invasion of privacy. |

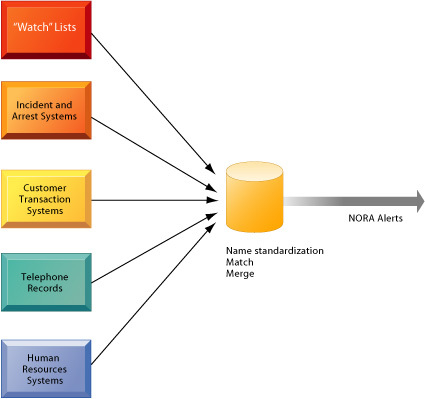

A new data analysis technology called nonobvious relationship awareness (NORA) has given both government and the private sector even more powerful profiling capabilities. NORA can take information about people from many disparate sources, such as employment applications, telephone records, customer listings, and “wanted” lists, and correlate relationships to find obscure hidden connections that might help identify criminals or terrorists (see Figure 5-2).

|

| FIGURE 5-2 Nonobvious

Relationship Awareness (NORA) NORA technology can take information about people from disparate sources and find obscure, nonobvious relationships. It might discover, for example, that an applicant for a job at a casino shares a telephone number with a known criminal and issue an alert to the hiring manager. |

NORA technology scans data and extracts information as the data are being generated so that it could, for example, instantly discover a man at an airline ticket counter who shares a phone number with a known terrorist before that person boards an airplane. The technology is considered a valuable tool for homeland security but does have privacy implications because it can provide such a detailed picture of the activities and associations of a single individual (Barrett and Gallagher, 2004).

Last, advances in networking, including the Internet, promise to reduce greatly the costs of moving and accessing large quantities of data and open the possibility of mining large pools of data remotely using small desktop machines, permitting an invasion of privacy on a scale and with a precision heretofore unimaginable. If computing and networking technologies continue to advance at the same pace as in the past, by 2023 large organizations will be able to devote the equivalent of a contemporary desktop personal computer to monitoring each of the 350 million individuals who will then be living in the United States (Farmer and Mann, 2003).

The development of global digital superhighway communication networks widely available to individuals and businesses poses many ethical and social concerns. Who will account for the flow of information over these networks? Will you be able to trace information collected about you? What will these networks do to the traditional relationships between family, work, and leisure? How will traditional job designs be altered when millions of “employees” become subcontractors using mobile offices for which they themselves must pay?

In the next section we consider some ethical principles and analytical techniques for

dealing with these kinds of ethical and social concerns.